- Mission Statement

Firestarter

Francesca Albanese

Lorem ipsum

Sheila Sheikh explores the role of cultural institutions in staging debates regarding emancipatory engagements with legal systems.

Against the backdrop of global inaction to prevent and cease the current genocide and ecocide in Gaza, and with this a resounding death knell of international law and human rights, the question of the relationship between law and politics, of legalism (i.e., adherence to law) in the service of anti-colonial resistance, intensifies. While there have recently been inspirational attempts – notably by the Hague Group, ‘a global bloc of states committed to “coordinated legal and diplomatic measures” in defense of international law and solidarity with the people of Palestine’ – to take an effective, exemplary position where other nation-states and international bodies shun responsibility, the question resists easy resolution. This does not, however, detract from its urgency. As I write, the temporal horizon includes both the emergency of genocide and mass starvation, on the one hand, and the terrifying institutional slowness of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC), on the other.1 And yet, despite their apparent hollowness, we might well say that law and rights are ‘that which one cannot not want.’2 The question then is how, in what form, and in what relations of power and political struggle one might want them.

There would be many ways to respond to this, depending on one’s position – for instance, between those who bear rights and those responsible for recognising and ensuring those rights, between those who defend human rights and civil society,3 between those who critique law and those who practise it, and so on – and my aim here is to begin to think through how a cultural institution such as Ibraaz might provide a meaningful space for such a debate. But allow me to begin elsewhere. As an academic who draws from the writings of critical legal scholars and who takes the claims and demands of anti-colonial activists seriously,4 I find myself drawn to the persistent question for scholars of international law, in particular those of the critical legal tradition, of whether to denounce Israel’s attacks on Gaza on the basis of their illegality, or whether to denounce the very system of international law. I suggest that this debate could function as a productive starting point from which to consider the role of academics more broadly, as well as artists, cultural workers, and activists – in conversation with practising lawyers – and, as I am coming to, to do so in the context of London.

Scholars of Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), for instance, have long shown that ‘international law is a working structure of global domination, one that reproduces colonial hierarchies, racialized exclusions, and gendered violence’ and that ‘international law fails every day’. As many have noted, and as is a recurrent topic in a 2024 dossier dedicated to international law and Gaza, well-meaning gestures of appealing to international law ‘ultimately sustain and reproduce the inequitable structure of international legal argumentation that generally upholds the colonial and capitalist underpinnings of liberal legalism’, to cite from legal scholar Nora Jaber’s contribution.

Here, in the case of the UK, history repeats itself: in 2003, legal scholars penned an open letter opposing the US and British invasion of Iraq using the language of law, which subsequently prompted much reflection on their own part that they had unintentionally appeared to champion an international law that they in fact wished to critique. The question thus looms large, over 20 years on, of what approach to take: to cite Jaber once again, there is on the one hand a desire ‘to turn away from the liberal international legal order and toward more emancipatory sites of resistance’. While I subscribe to this, I simultaneously wish to retrieve the counter-hegemonic potential of international law, especially when put to use from below – its possibility to be used as a tool in the service of political resistance and a horizon of decolonisation, to be ‘part of [a] future story that is yet to be written’.

To remain a moment with the critical legal: one way of responding to this conundrum is to begin by clarifying the difference between ‘tactics’ (short-term action, for instance, legalism or reform) and ‘strategy’ (longer-term intervention, including revolution – the kind of critique signalled above by Jaber), as helpfully elucidated by legal scholar Robert Knox in an oft-cited 2010 article, ‘Strategy and Tactics’.5 Here I propose that people’s tribunals are exemplary spaces through which to think through and experiment with the relationship between the two approaches and even, potentially, to follow the lead of TWAIL scholars for whom, as Luis Eslava writes, the struggle ‘must always be about present “tactics”, and about a longer “strategy”’. I contend that people’s tribunals and staged hearings (fictive or ‘mock’ trials) are ideal spaces in which to tease out dilemmas around what legal scholar Tor Krever calls the ‘juridification of resistance’, and to rehearse possible avenues for seeking justice within and beyond the realm of law and rights.

While in recent months there have been two Gaza Tribunals (one international tribunal is ongoing and one took place in London on 4–5 September), I will not engage with these here. Rather, due to the particularity of their form and framing, I turn to two events that took place in West London simultaneously over a weekend in April this year and that each held Gaza in the backdrop – the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes and the People’s Tribunal on Police Killings – to explore two differing, but highly critical approaches to human rights, (international) law, and their colonial and liberal underpinnings. Krever has argued that in people’s tribunals after the moment of Third World movements and anticolonial internationalism, the liberal (i.e., neutral and apolitical) language of international law and human rights has displaced other emancipatory frameworks in the political imagination of internationalism.6 However, I posit that during the course of this weekend in London, between these two events, glimpses of an alternative political imagination could be discerned.

The Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), established by lawyer, scholar, and activist Radha D’Souza and artist–researcher Jonas Staal, is a project that ‘stages public hearings in immersive installations functioning as a court, to prosecute intergenerational [i.e., past, present, and future] climate crimes committed by states and corporations acting together’.7 It does this through the form of a ‘more-than-human tribunal’ that includes the representation of extinct species and non-human agents such as plants, alongside judges and a public jury, composed of the audience, that is tasked with passing a verdict based on the Intergenerational Climate Crimes Act, the legal foundation of the work, which assembles and supplements progressive elements of legal and political thought such as the rights of nature, interdependency, the rights of future generations, transformative justice, and so on.8

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes: The British East India Company on Trial, 2025, Serpentine Galleries Ecologies. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes: The British East India Company on Trial, 2025, Serpentine Galleries Ecologies. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

This particular chapter, titled The British East India Company on Trial, was the third iteration of the project, following hearings in Amsterdam in 2021 and Gwangju in 2023, each time in arts spaces. Staged at the Ambika P3 space at the University of Westminster on Marylebone Road from 4 to 6 April (an off-site commission of the Serpentine Gallery), the hearing set its sights close to home: on the enduring legacies of the British East India Company (EIC, which was founded in 1600 and ceased to exist as a legal entity in 1873) ‘for extractive capitalism and imperialism, perpetuating ecological collapse’.9 During three cases (videos of which are available online), the public jury heard from and posed questions to a variety of witnesses – representing campaign groups, grassroots organisations, human rights organisations, environmental groups, researchers, scholars, and journalists – ‘regarding the crimes committed by the British East India Company, highlighting the interconnectedness of colonial and climate crimes that continue to shape our devastating present and future’. These included the destruction of ecologies and communities; the establishment of agribusiness and destruction of interdependent ecologies; and the violent severance of land–people relationships.

Knox delineates the difference between tactical approaches to international law, which end up capitulating to liberal legalism, and strategic approaches, which have longer term, structural objectives. To paraphrase Knox, these latter stand in distinction to a liberal, mainstream, or ‘common sense’ understanding of law that sees it as a ‘neutral’ vessel that can end relations of exploitation and domination (notably colonial). In other words, rather than seeing law as a set of specific rules, strategic approaches understand law as a structure – a relationship between law and social phenomena – that constitutes and enables the relations that critical legal scholars wish to fight.10 This liberal understanding of law chimes with D’Souza’s critique of liberalism as the foundation of modern law and human rights (and as a political system), in her 2018 book, What’s Wrong with Rights? Social Movements, Law and Liberal Imaginations, which forms the conceptual basis for the CICC.11

Moving from human rights to climate crimes, the CICC was established precisely ‘to critique the liberal legal system that privileges states and corporations over ecologies and communities’ and that has ‘resulted in intergenerational injustice against natures and peoples around the world’. Rather than pursuing a project that diagnoses how the activities of the British East India Company and the corporations in its wake were/are illegal and must be contested in these terms (i.e., the tactical approach), the project takes the strategic line insofar as it proposes that if one is to strive for intergenerational climate justice, one needs an altogether different understanding and practice of law through which to define and judge the crimes in question.

Essentially, as D’Souza outlined in her introductory speech on the opening evening, it is the law itself that is on trial here,12 a gesture inspired by key historic moments in which people have put the law on trial: national liberation movements, the slaves of Haiti, working people in the UK when they demanded a people’s law. And for this trial to be possible, a collective fabulation is necessary – one that conjures the potential of establishing intergenerational relationships of solidarity. Against the ‘real’ legal fictions of actually existing law (for instance, the legal personhood of corporations), the fictional hearing proposed a different legal imaginary, functioning as a form of prefigurative politics or politics of the subjunctive, as if it were possible to pass judgement on the British East India Company, as if the Intergenerational Climate Crimes Act and its statutes existed, and hence as if international human rights law and environmental law weren’t part of the problem.

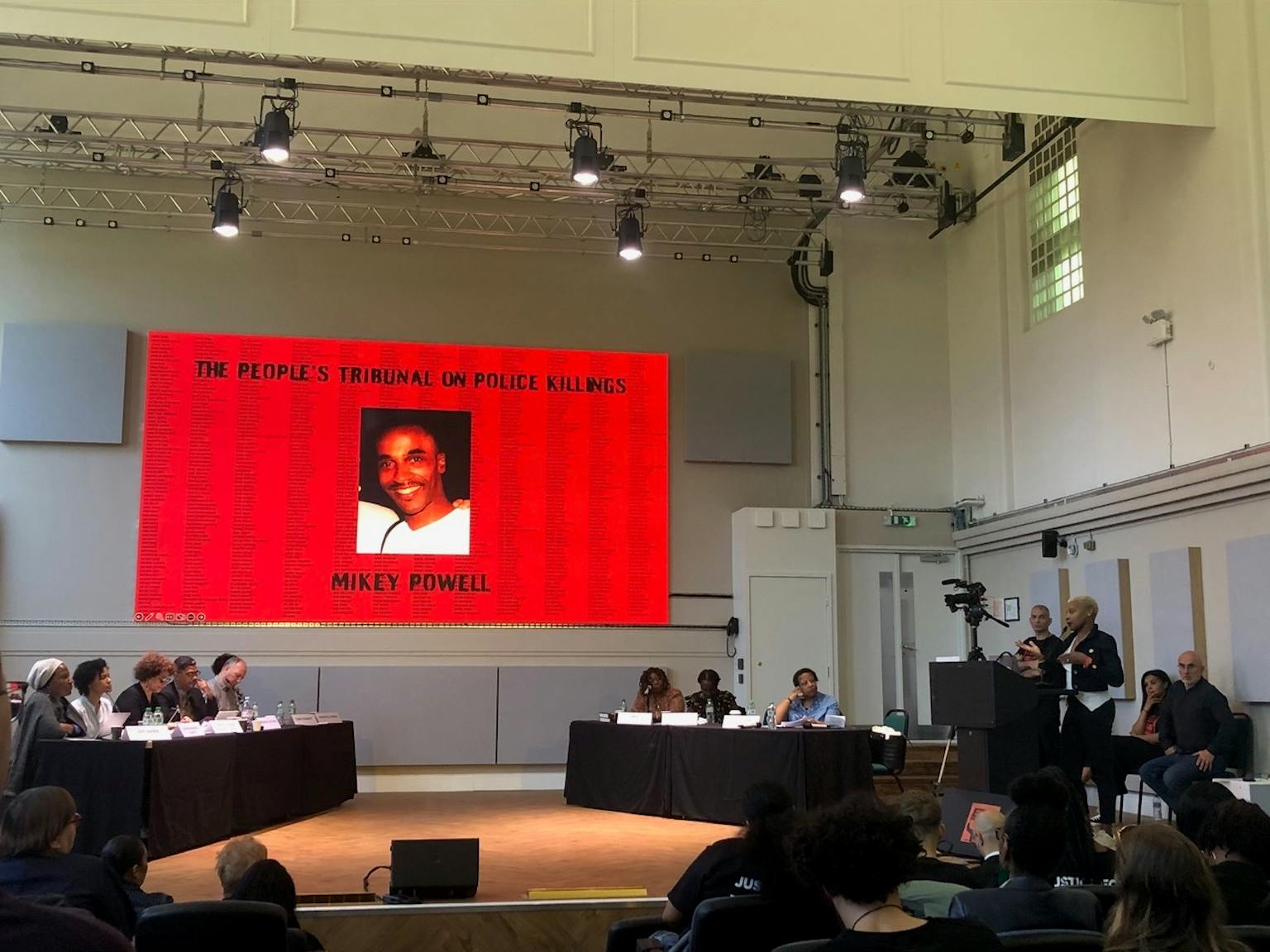

That same weekend, less than half a mile’s walk away at a Regent’s Park venue, the People’s Tribunal on Police Killings (PTPK) was taking place. Led by the families of those killed and supported by the United Friends and Families Campaign, Migrant Media, and 4WardEverUK, with the assistance of Black Lives Matter UK,13 the tribunal assembled families and loved ones of 28 victims of police killings,14 and was organised with the aim of seeking recognition of the extent to which the British state has failed to protect its own citizens, and of ‘“exposing the extent of the injustice” and placing it on the international stage’. The tribunal called attention to the disproportionate number of Black people killed and the fact that, while there have been approximately 3,000 deaths in the UK at the hands of the police since 1971, only four prosecutions have led to the police officers responsible being convicted. On the stage of the auditorium, family members gave testimonies about how their loved ones died, their subsequent treatment by the police and legal system, and the impact this had on them. This was interspersed with contextual contributions from expert witnesses,15 responses from an international tribunal panel,16 and offerings from the two organisers, who had worked for several years with a group of mainly young volunteers to put together the event: Ken Fero (of Migrant Media) and Samantha Patterson (sister of Jason McPherson, who was killed in 2007 at London’s Notting Hill police station).17

The People’s Tribunal on Police Killings (PTPK), Day 1, London, 5 April 2025. Courtesy of the author.

Families of victims of police killings demonstrate in London in 2003. Photo: Migrant Media.

The tribunal is just one part of an international 10-year plan that includes three further tribunals (on prison killings, immigration detention, and secure medical units) and a three-pronged focus on international criminal law, the United Nations, and domestic legislation. The broader aim of the tribunal is to instigate the re-opening of several thousand police killings in the UK, to include pursuing a class-action lawsuit against the British police officers, police chiefs, government departments, and individuals responsible. As Fero outlines, the campaign is internationalist in outlook, explicitly linking police killings in the UK to those in Europe, the US, Brazil, and Palestine through the contributions of the tribunal panel, and citing earlier people’s tribunals such as the Russell Tribunal on Vietnam and the Russell Tribunal on Palestine as inspiration.18

Let us return to the question of tactical and strategic interventions. The tribunal and the larger project, of which it is a part, perform both, enacting what Knox calls a ‘principled opportunism’ whereby the (tactical) deployment of a legal argument is in the service of longer-term strategic political exigencies and, in Krever’s words regarding the 1967 Russell Tribunal on Vietnam, legalism is ‘mobilized in aid of the tribunal’s broader practice of resistance against imperialism’ – to which we can here add state racism.19 Therefore, we might read the PTPK as a 21st-century response to the ‘potential history’ of the 1967 Russell Tribunal, a potentiality that has been dampened with the shift to a depoliticised language of liberal human rights. Where the CICC functioned in the register of the ‘as if’, we might say that the PTPK inhabited the ‘what if?’

The CICC’s speculative hearings, which function alongside ‘real’ legal cases against governments and corporations, allow for a wholesale reimagination of the law through the fictional CICC Act. In the absence of a reimagined legal system and in the urgency of justice for the numerous victims and their families, the PTPK, a ‘real’ people’s tribunal,20 remained within the existing legal system, demonstrating the repeated illegality of the police’s actions and essentially asking: what if the international legal system as it currently stands could be held accountable for the crimes (killings) and injustices (subsequent treatment of victims’ families) that the British state, through its agents, continues to commit? What if numerous victims’ families and loved ones came together to appeal to the law as it exists (all of this sounds like the tactical approach), but to also use the law to do something unprecedented (the class-action lawsuit would be the first of its kind), changing the narrative around it and – essentially, insofar as the eventual lawsuit would be against the representatives of the law – strategically putting the law itself on trial.

Through the discursive space of the people’s tribunal (this being one of the main opportunities afforded by such assemblies), the various speakers were able to show both the crimes committed (to argue for these being ‘killings’ rather than use the liberal language of ‘deaths in police custody’) and to provide a convincing case, in particular through the expert witnesses’ contributions, for the structural racism of the state and its policing institutions. This was also made evident through the dramaturgy of the two days: while each testimony was shattering in and of itself (an affective weight hung heavy in the air of the hall throughout the weekend), the power of the event lay in assembling numerous testimonies into an unfinished chorus that itself testified to systematic, structural injustice and that refused the dominant media narrative of individual cases.

As Fero and Patterson insist, this is not about legal reform or new legislation that have failed again and again over the decades and are a mere distraction, but is about revolution: in using the law opportunistically, legalism is a means through which, to quote the organisers, to ‘take forward the heritage of families struggle in a way that radically challenges the status quo’, to ‘implement a series of actions to make the real revolutionary change that is needed.’ Moreover, besides encompassing both tactical and strategic approaches to the law through principled opportunism, the tribunal performed an impressive balancing act of holding space both for those for whom justice would be seeing the law applied ‘correctly’ (i.e., guilty police officers prosecuted) and for those for whom justice remains elsewhere, beyond the law, not as punitive justice but as a transformative justice that centres police and prison abolition,21 and an epistemic justice that provides space for families and loved ones to rehearse their testimonies on their own terms.22

To conclude, let us return to the potential of a new cultural space in London. While people’s tribunals such as the recent Gaza Tribunal in London are crucial for assembling expert witnesses and first-hand witnesses and, in this case, arguing not only for the UK government’s complicity in genocide but its participation, I argue that people’s tribunals can also open longer-term, strategic lines. Knox ends ‘Strategy and Tactics’ by asking what the role of critical scholars is, suggesting that ‘they can help shape the campaigns of other radicals, who often cleave to a rhetoric of liberal legalism,’ and making reference to a capacity to write in a manner that renders complex theory legible in the broader international political arena. As we saw with the CICC, D’Souza, a legal scholar, took this one step further, dramatising and aestheticising the critique of international law and staging a speculative alternative that the audience could actively participate in. This she did, in collaboration with Staal, precisely through the infrastructure of art, which allows for far greater freedom than most academic spaces to assemble a range of practitioners and to frame, narrate, and advertise such a gathering as an ‘event’ to be conceptually engaged with.23

At present, many artists are exploring the relationship between art and law, including through the tribunal form. As Ibraaz opens its new space, one of many challenges would be how to programme works and events that do not simply represent the troubled relationship between law and politics that I began with (whether this be in relation to Palestine or otherwise), but that actively engage in the challenge of combining tactical and strategic analysis and intervention in the name of anti-colonial resistance.

Knox suggests that critical scholars need to focus on how their ‘critique’ can reach a broader community of activists and political actors but, as we have seen with the PTPK, seasoned activists and political actors have much to teach scholars, lawyers, and artists about principled opportunism and people’s justice, about how to negotiate the law as ‘that which we cannot not want.’ While some individuals of a certain privileged mobility can move with little friction between art and grassroots activist spaces, the challenge for this new cultural institution is how to ensure that this traffic is bi-directional and to cultivate reciprocal, non-extractive relations in a project of collectively assembling alternative legal and political imaginaries.

* I extend my thanks to Anthony Downey for commissioning this text and giving me opportunity to think through these issues in writing, and to Niamh Dunphy for the careful copy-edit.

Francesca Albanese

Jonas Staal, Nadja Argyropoulou, Basma al-Sharif

Anthony Downey